Further JS: the DOM and bundlers

- VSCode

- Web browser

JavaScript is a programming language that allows you to implement complex things on web pages. Every time a web page does more than sit there and display static information – e.g., displaying timely content updates, interactive maps, animated graphics, scrolling video jukeboxes, etc. – you can bet that JavaScript is probably involved.

In this section of the course, we will be dealing with client-side JavaScript. This is JavaScript that is executed by the client’s machine when they interact with a website in their browser. There is also server-side JavaScript, which is run on a server just like any other programming language.

The Final Piece of the Puzzle

If HTML provides the skeleton of content for our page, and CSS deals with its appearance, JavaScript is what brings our page to life.

The three layers build on top of one another nicely – refer back to the summary in the Further HTML and CSS module.

The JavaScript language

The core JavaScript language contains many constructs that you will already be familiar with.

Read through the MDN crash course to get a very quick introduction to all the basics. If you already know Java or C#, some of the syntax may look familiar, but be careful not to get complacent – there are plenty of differences!

Of course, there is a huge amount you can learn about JavaScript (you can spend an entire course learning JS!) However, you don’t need to know all the nuances of the language to make use of it – writing simple functions and attaching event listeners is enough to add a lot of features to your web pages.

How do you add JavaScript to your page?

JavaScript is applied to your HTML page in a similar manner to CSS. Whereas CSS uses <style> elements to apply internal stylesheets to HTML and <link> elements to apply external stylesheets, JavaScript uses the <script> element for both. Let’s learn how this works:

Internal JavaScript

First of all, make a local copy of the example file apply-javascript.html. Save it in a directory somewhere sensible. Open the file in your web browser and in your text editor. You’ll see that the HTML creates a simple web page containing a clickable button. Next, go to your text editor and add the following just before your closing </body> tag:

<script>

// JavaScript goes here

</script>

Now we’ll add some JavaScript inside our <script> element to make the page do something more interesting – add the following code just below the // JavaScript goes here line:

function createParagraph() {

var para = document.createElement('p');

para.textContent = 'You clicked the button!';

document.body.appendChild(para);

}

var buttons = document.querySelectorAll('button');

for (var i = 0; i < buttons.length ; i++) {

buttons[i].addEventListener('click', createParagraph);

}

Save your file and refresh the browser – now you should see that when you click the button, a new paragraph is generated and placed below.

External JavaScript

This works great, but what if we wanted to put our JavaScript in an external file?

First, create a new file in the same directory as your sample HTML file. Call it script.js – make sure it has that .js filename extension, as that’s how it is recognized as JavaScript. Next, copy all of the script out of your current <script> element and paste it into the .js file. Save that file. Now replace your current <script> element with the following:

<script src="script.js"></script>

Save and refresh your browser, and you should see the same thing! It works just the same, but now we’ve got the JavaScript in an external file. This is generally a good thing in terms of organizing your code, and making it reusable across multiple HTML files. Keeping your HTML, CSS and JS in different files makes each easier to read and encourages modularity and separation of concerns.

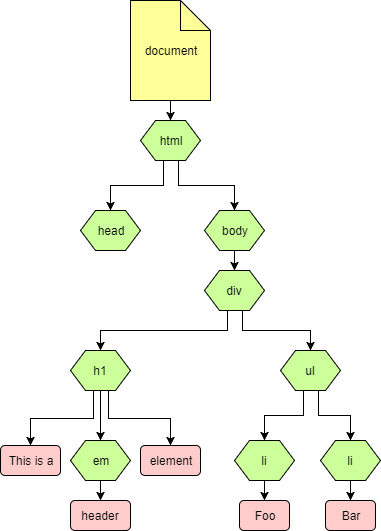

DOM Elements and Interfaces

The DOM (Document Object Model) is a tree-like representation of your HTML structure, containing nodes of different types, the most common being:

- Document Node – the top level node containing your entire web page

- Element Node – a node representing an HTML element, e.g. a

<div> - Text Node – a node representing a single piece of text

Each node will implement several interfaces which exposes various properties of the node – e.g. an Element has an id corresponding to the id of the HTML element (if present).

Consider this fairly simple HTML document:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head></head>

<body>

<div>

<h1>This is a <em>header</em> element</h1>

<ul>

<li>Foo</li>

<li>Bar</li>

</ul>

</div>

</body>

</html>

Follow the Manipulating documents guide to learn how to obtain and manipulate DOM elements in JavaScript.

The DOM is not intrinsically tied to JavaScript or HTML: it is a language-agnostic way of describing HTML, XHTML or XML, and there are implementations in almost any language. However, in this document we are only considering the browser implementations in JavaScript.

DOM Events

By manipulating DOM Elements you can use JavaScript to manipulate the page, but what about the other way around?

Manipulating the page can trigger JavaScript using DOM Events.

At a high level these are relatively straightforward: you attach an Event Listener to a DOM element which targets a particular event type (‘click’, ‘focus’ etc.). There are 3 native ways of attaching event listeners:

addEventListener

var myButton = document.getElementById('myButton');

myButton.addEventListener('click', function (event) { alert('Button pressed!'); });

Any object implementing EventTarget has this function, including any Node, document and window.

While it may appear the most verbose, this is the preferred method as it gives full control over the listeners for an element.

To remove a listener, you can use the corresponding removeEventListener function – note that you need to pass it exactly the same function object that you passed to addEventListener.

Named properties

var myButton = document.getElementById('myButton');

myButton.onclick(function (event) { alert('Button pressed!'); });

Many common events have properties to set a single event listener.

HTML attributes

<button id="myButton" onclick="alert('Button pressed!')">My Button</button>

The named properties can also be assigned through a corresponding HTML attribute.

This should generally be avoided as it has the same issues as named properties, and violates the separation of concerns between HTML and JavaScript.

The Event interface

As hinted by the examples above, event listeners are passed an Event object when invoked, containing some properties about the event.

This is often most important for keyboard events, where the event will be a KeyboardEvent and allow you to extract the key(s) being pressed.

Event propagation

<div id="container">

<button id="myButton">My Button</button>

</div>

Adding a ‘click’ event listener to the button is a fairly simple to understand, but what if you also add a ‘click’ event listener to the parent container?

var container = document.getElementById('container');

container.addEventListener('click', function (event) {

alert('Container pressed?');

});

var myButton = document.getElementById('myButton');

myButton.addEventListener('click', function (event) {

alert('Button pressed!');

});

In particular, does a click on the button count as a click on the container as well?

The answer is yes, the container event also triggered!

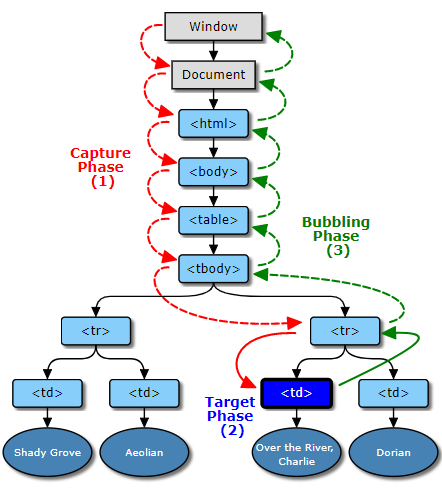

The precise answer is a little involved. When an event is dispatched it follows a propagation path:

The full documentation can be found here, but as a general rule, events will ‘bubble’ up the DOM, firing any event listeners that match along the way. However there is a way of preventing this behaviour:

event.stopPropagation()

var myButton = document.getElementById('myButton');

myButton.addEventListener('click', function (event) {

event.stopPropagation(); // This prevents the event 'bubbling' to the container

alert('Button pressed!');

});

Now if we click the button, it won’t trigger the container listener.

Use stopPropagation sparingly! It can lead to a lot of surprising behaviour and bugs where events seemingly disappear. You can usually produce the desired behaviour by inspecting event.target instead.

From the diagram above, there is another phase – the capture phase, which can be used to trigger event listeners before reaching the target (whereas bubbled events will trigger listeners after reaching the target).

This is used by setting the useCapture argument of addEventListener:

var container = document.getElementById('container');

container.addEventListener('click', function (event) {

alert('Container pressed?');

}, true); // useCapture = true

Now the container event listener is fired first, even though the button event listener is stopping propagation.

You can also call stopPropagation in the capture phase, to prevent the event reaching the target at all. This is rarely useful unless you genuinely want to disable certain interactions with the page.

Use capturing with caution - it is fairly uncommon so can be surprising to any developers who are not expecting it.

Default behaviour

Many HTML elements and events have some kind of default behaviour implemented by the browser:

- Clicking an

<a>will follow the href - Clicking a

<button type="submit">will submit the form

These can be prevented by using event.preventDefault():

<a id="link" href="http://loadsoflovelyfreestuff.com/">Free Stuff!</a>

var link = document.getElementById('link');

link.addEventListener('click', function (event) {

event.preventDefault();

alert('Not for you');

});

If you attempt to click the link, the default behaviour of following the link will be prevented, and instead it will pop up with the alert.

It is important to understand the difference between preventDefault() and stopPropagation() – they perform very different tasks, but are frequently confused:

preventDefault()stops the browser from performing any default behaviourstopPropagation()stops the event from ‘bubbling’ to parent elements

JavaScript or ECMAScript?

You may have come across the term ECMAScript (or just ‘ES’, as in ‘ES6’) when reading through documentation and wondered exactly what it means. The main reason to know about it is for knowing whether a particular feature is usable in a certain browser.

ECMAScript refers to a set of precise language specifications, whereas JavaScript is a slightly fuzzier term encompassing the language as a whole.

In practice JavaScript is used to refer to the language, and ECMAScript versions are used to refer to specific language features. Depending on the implementation, a JavaScript engine will contain features from the ECMAScript standards, as well as some common extensions.

There are currently several important revisions of the ECMAScript standard:

- ECMAScript 5.1

- ECMAScript 6 (also called ECMAScript 2015)

- Yearly additions: ECMAScript 2016, 2017… 2022

ECMAScript 5.1

ECMAScript 5.1 is synonymous with ‘standard’ JavaScript, and is fully supported by every major browser with a handful of very minor exceptions.

If a feature is marked as ECMAScript 5 you can safely use it in your client-side JavaScript without worrying.

ECMAScript 6

ECMAScript 6 introduces a lot of modern features: block-scoped variables, arrow functions, promises etc.

These are fully supported by the latest versions of Chrome, Firefox, Edge, Safari and Opera. However, older browsers, in particular Internet Explorer, will not support them.

Usually with a process called transpilation, most commonly using Babel, older browsers can use ES6+ features. Although the topic is too large to cover in detail here, a JavaScript transpiler can (attempt to) transpile code containing ES6 features into an ES5 equivalent (very similar to the way SASS/Less is compiled to plain CSS). However, there are a few language features it cannot reproduce, so it still pays to be careful. For features like new types/methods, transpilation is insufficient and instead one needs to add polyfills (also supported by Babel).

The good news is that the situation here is changing rapidly! The market share of browsers incompatible with ES6 (primarily IE) is somewhere between 2-3% at the end of 2022, but falling continuously. Moreover, Internet Explorer 11 was officially retired in 2022, so most websites tend to use ES6 features natively nowadays.

ECMAScript 2016+

Between ECMAScript 2016 and 2022, many important features were added. Probably the most well known is async/await syntax (added in 2017).

If this all sounds confusing, it is! If you’re in doubt, caniuse.com allows you to search for a feature and see which browsers support it. MDN documentation usually has a compatibility table at the bottom as well.

Bundlers

A JavaScript bundler is a tool that takes multiple JavaScript files and combines them into a single file, that can be served to the browser as a single asset. This can improve performance by reducing the number of HTTP requests required to load a web page. Bundlers can also perform other optimizations, such as minifying the code (removing unnecessary characters to make the file smaller) and tree shaking (removing unused code).

There are several popular JavaScript bundlers available:

These tools typically use a configuration file to specify which files to bundle and how to bundle them.

Further reading

JavaScript is a huge topic, so don’t worry if you feel like you’re only scratching the surface. Focus on getting used to the syntax and learning some of the cool things it can do.

Have a look at the JavaScript Building Blocks and JavaScript Objects articles on the MDN JavaScript course. There’s a lot of material there, but if you have time it will give you a more solid grounding in JavaScript.